If you’re wondering how the teachings of a little-known early-20th-century dentist can possibly be relevant for the lifelong health of your (future) baby, or what really constitutes “super foods”, then read on!

There’s a good number of people out there who think that we live in a golden age of health and longevity thanks to advances in medical science. I would know because I used to be one of them. The daughter of a doctor, my childhood was punctuated by visits to the doctor and popping antibiotics without giving it a second thought. Until well into my adult years, I was convinced that caring about your health meant that you periodically consulted somebody in a white suit and dutifully filled their prescriptions.

It wasn’t until fairly recently that I started entertaining a different notion of what being in good health really means. While it may seem like it’s a good thing that people are living longer than ever today, when we stop to consider the quality of those lives, the picture starts becoming murkier. Not a day goes by when we don’t hear about “diseases of civilization” like diabetes, heart disease, cancer, obesity and a whole host of chronic ills taking over the developed world. Neither is the developing world spared as they become wealthier and start adopting Western ways at the expense of their traditional cuisines and lifestyles. Add to this the shocking prediction that children born in the US today may have a shorter life expectancy than their parents, my previous assumptions about health start seeming naïve to say the least.

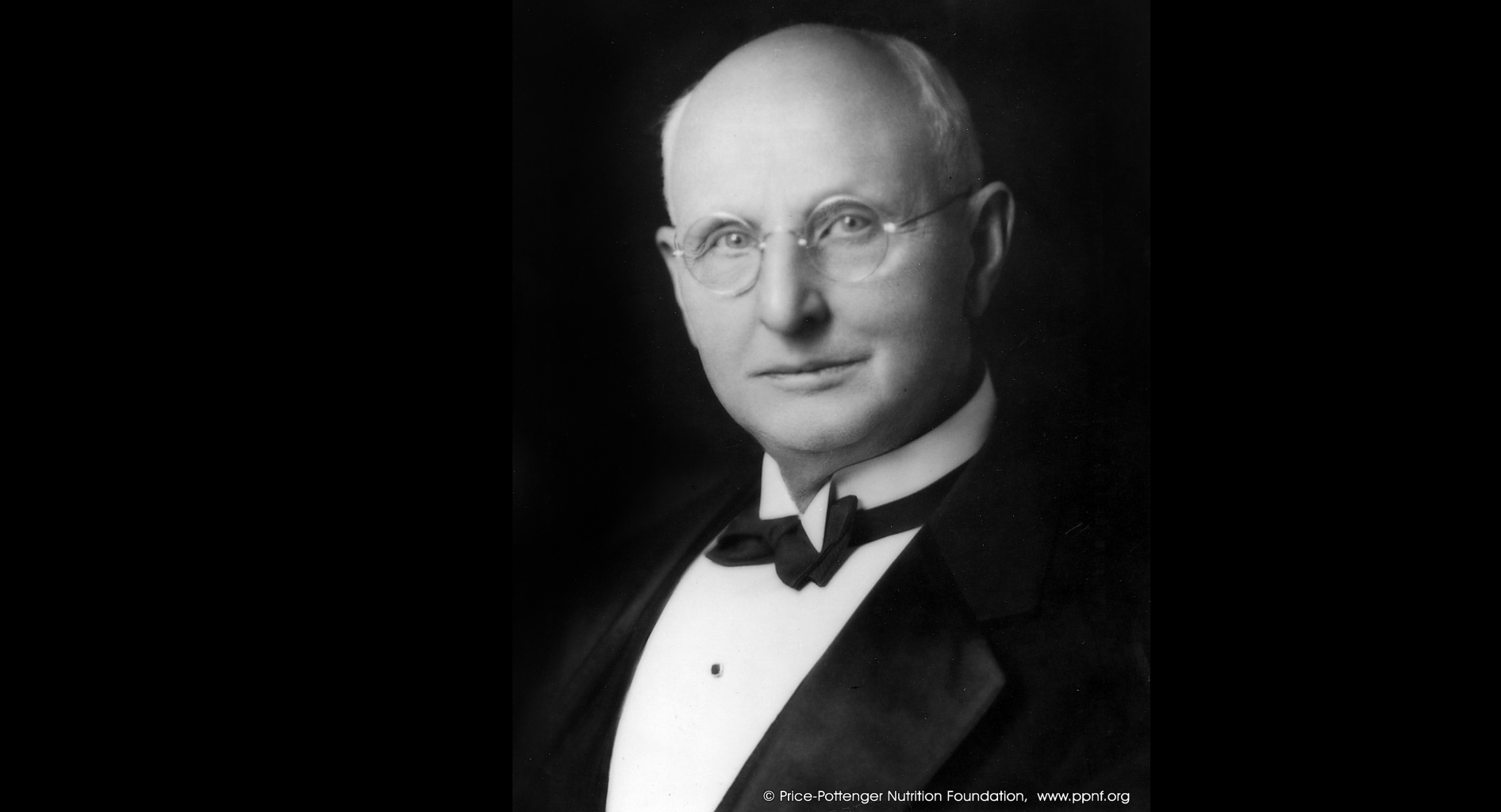

I spoke elsewhere about my growing interest in holistic health and nutrition since my pregnancy a few years ago. The evolution in my thinking was very much influenced by an understanding of human health from a historical and anthropological perspective. This is where the fascinating findings of Weston A. Price come in. In fact when you find out more about him and his work, it seems criminal that he’s not a household name today given that he was bemoaning the advent of modern convenience foods and their catastrophic effects on human health all the way back in the 1930s.

So who exactly was Weston A. Price? He was a Cleveland dentist and the head of the National Dental Association (precursor of the research arm of the American Dental Association) who was becoming increasingly concerned by the poor dental health of children coming through his practice. In the span of just one generation, the incidence of dental caries, dental arch malformations and overall disease had become disturbingly common. Now, he had a hunch about all this and wondered if the root causes of these problems could not be traced back to poor nutrition and whether the modern diet, with its cheap baked goods, sugary fare and increasing use of vegetable oils, was not lacking some “protective elements” that traditional diets of yore were able to capture.

Armed with his hypothesis, he undertook an ambitious study that took him to various remote corners of the world, places that were much more difficult to access than today, to study traditional cultures. His idea was to meet “primitive peoples” who had been relatively untouched by modern civilization and its newfangled convenience foods, and study the nutritional habits that they had practiced for generations. His 1939 book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration features the findings of his vast anthropological study to shed light on the nutritional underpinnings of human health.

Traveling extensively, accompanied by his wife, he seems to have left no stone unturned. His journeys took him from the remote corners of North America including Alaska, Canada and Hawaii to Polynesia, from Northern and Central Africa to Europe (yes there were still “untouched” populations in the heart of Europe back then), from South America to Australia and passing through New Zealand… In every place he went, he examined the dental health of the local population, checking for caries as well as the development of the dental arches. He kept detailed records and also took many photographs which are scattered throughout the book. He even took samples of traditional foodstuffs to examine their nutrient profile in the laboratory.

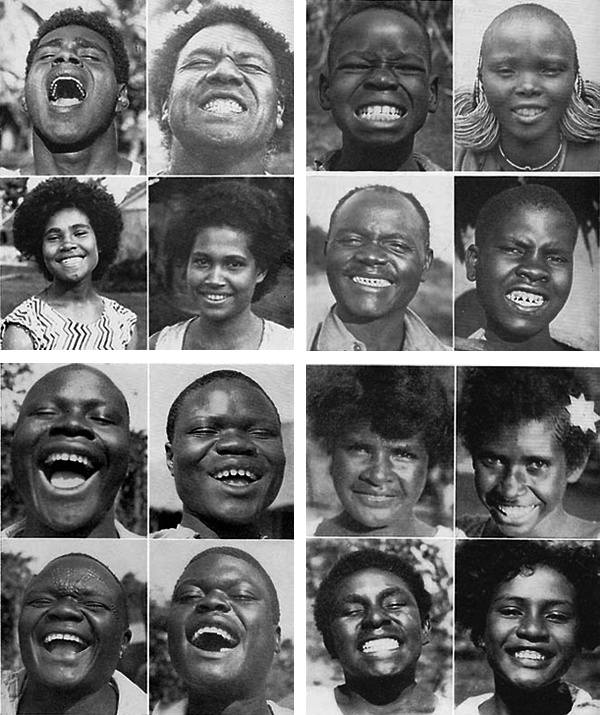

The populations he studied, their physical environments and respective diets could not be more diverse but what all these people had in common was that they had perfectly adapted to their own unique environment by maximizing the bounty of the earth to meet their needs. And by “needs” we’re talking about something no less ambitious than the will to produce robust, well-built individuals, while having none of the access to medical technology that Western populations were already starting to take for granted. Because in every isolated group he studied, he encountered people who had excellent facial and dental formations, were virtually free of dental problems as well as the many chronic and infectious diseases ravaging modern populations of the day.

The broad, well-formed faces of the typical members of these societies are on display in these photos (clockwise from top left: Pacific Islanders, Kenyan tribes, Torres Strait islanders, West Nile tribe):

So what does this all have to do with fertility and making robust babies?

Well here’s what’s even more remarkable: by all accounts, the traditional diets were amazingly nutritious and superior in every way to our modern-day diets. And yet when it came to fertility, they did not content themselves with even this and actually went to great lengths to ensure that the new generation would be as healthy and robust as possible. They did this by paying special attention to the fertility period and feeding women and sometimes even men of childbearing age particular super foods, with an emphasis that began even before conception.

This means that they understood instinctively, through generations of trial and error, that there was a nutritional “code” to crack and they had to use food as a means of lifelong health insurance for their offspring.

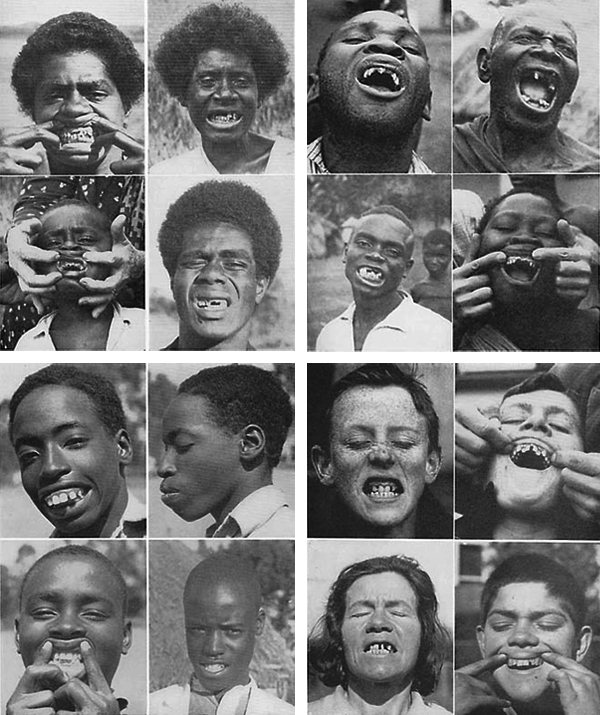

Here’s where his study was so well-designed and is so crucial today: being the clever man that he is, he did not content himself with simply comparing these societies with their Western counterparts (which would have been impressive enough). Instead, at each stop of the way, he endeavored to find populations of the same “racial stock” who for their part had been exposed to modern foods for some period of time. This provided him with the perfect control group since any differences in health and development (dental and otherwise) could not then be attributed to confounding factors like differences in genetic pool. Lo and behold, his examination of these people yielded something very similar to what he had been observing back home: rampant tooth decay, dental, facial and other skeletal malformations, developmental problems and a high incidence of infectious and chronic diseases like tuberculosis and cancer.

So beyond not having been introduced to the dubious pleasures of modern convenience foods, just what was it that the isolated traditional societies were eating that was doing so much for their well-being? After all, Weston Price was after discovering the protective factors that these traditional diets were providing these people and their children. So what was the code? And were there any similarities between the diverse groups?

I will talk more about that and the famous traditional fertility diets in the second part of this series. Stay tuned!